The following story is adapted from multiple sources: Ethel Wallis’ 1959 book “Two Thousand Tongues to Go,” which recounts the story of Wycliffe Bible Translators, the 1960 “Navajo New Testament” feature originally published in Translation magazine (March 1960, reprint) and portions of Ethel Wallis’ later book, “God Speaks Navajo.” Together these accounts highlight the progress of the Navajo translation team, led primarily by Faye Edgerton and other women.

A Heart for the People

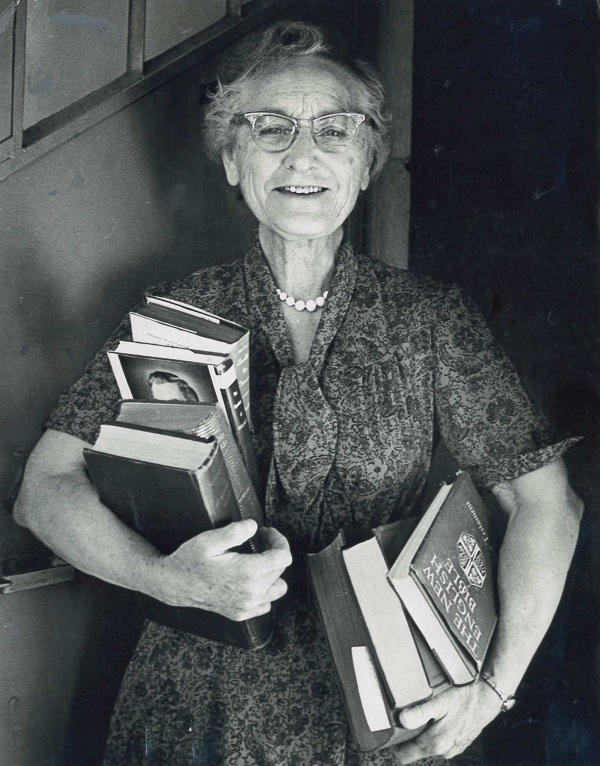

Veteran of the Navajo translation team, Faye Edgerton was a gentle, gray-haired lady nearing 70 — yet she could still be found walking briskly to a hogan (a traditional Navajo dwelling) to visit friends or driving her Volkswagen across the reservation.

“Her repeated winters” with the Navajos — to use their own expression — had produced an understanding love for them. She would go on to spend many more winters among the Navajo and the Apache, working with her translation partner, Faith Hill.

But Faye Edgerton did not begin her missionary career in the Arizona desert. As a young woman, she spent several years in Korea, only to have her mission work there prematurely terminated by an illness preventing her return to Asia. It was in 1924 that she went to live on the Navajo reservation.

During her service in Korea, she was impressed with one great fact: The faith of the Korean Christians was strong and contagious because they had the Bible in their own language. Hence, Christianity was no longer a foreign religion; it was distinctively Korean. That experience left her with a conviction that the Navajo, too, needed God’s Word in their own language.

Learning a Difficult Language

When Faye arrived on the Navajo reservation in 1924, few missionaries shared her vision. Navajo was a challenging language for English speakers to learn, with no written tradition at the time and few resources. Faye Edgerton learned slowly, studying only on rainy days when other mission activities were curtailed. But she was always listening, learning and trying to master the intricate language which intrigued her.

In 1941, while still searching for an efficient way to write and speak Navajo, she met Turner and Helen Blount. The three discovered a shared purpose — mastering Navajo to translate the New Testament.

They worked together on phonetics, sometimes debating over subtle sounds. Turner once suggested a “glottal stop” or “voiceless l” that Faye was missing, and she teased him that he was “hearing things.” After all, she had been studying the language a good deal longer than he!

But after attending the Summer Institute of Linguistics (now SIL Global) in 1942, she began to “hear” those sounds herself — and her spoken Navajo improved dramatically.

Building a Translation Team

In 1944, the trio joined Wycliffe Bible Translators and began a concentrated effort to complete the translation of the New Testament. In 1946, Faith Hill joined the Wycliffe team, followed in 1950 by Anita Wencker. The five worked steadily for a decade, each playing a role.

With Faye Edgerton carrying the main burden of the actual translation, other members of the team devoted themselves to literacy work and testing trial versions with their readers. Only a translation in genuine idiomatic Navajo would communicate the Scriptures to their hearts and minds — and not just be “the white man’s book of heaven” in white man’s Navajo!

One Navajo man who helped test trial translations was overheard telling a friend:

“This isn’t just a missionary talking to us in another language — this is God’s Word in Navajo. It is just like God talking! It is like a fire burning inside me.”

Challenges in Translation

Some passages were able to be translated smoothly, especially those about sheep and shepherding. These stories were familiar to people who had tended flocks for generations. Others were far more difficult.

In the story of Mary and Martha, for instance, the original language doesn’t state which sister was older — but Navajo grammar requires that detail. The translators concluded, based on Martha’s role in household responsibilities, that she was probably the older sister. The narrative then read naturally in Navajo as “Mary and her-older-sister-Martha.”

Another example is that when they were translating the references to musicians in Revelation 18:22, the team found equivalents in traditional Navajo instruments to make the imagery resonate without losing biblical meaning.

Translators worked to ensure the gospel was communicated to the Navajo in a way that resonated with their specific cultural and linguistic contexts without changing its core message. In Bible translation that continues to be essential to ensure the Scriptures communicate clearly and naturally to people.

Literacy: Opening the Word to the People

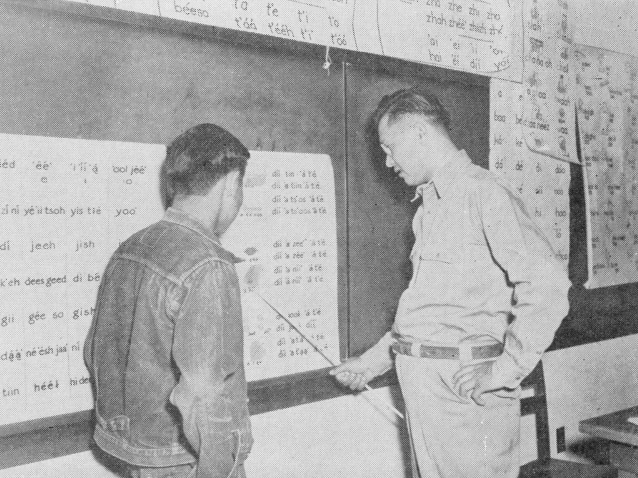

Translation was only part of the work — the people also needed to read it. Faith Hill and Anita Wencker developed primers, charts and storybooks in Navajo. Their living room walls were covered with reading charts, and few visitors left without a lesson. They took these materials to camps and trading posts, introducing written Navajo to people — many for the very first time.

One man, Sheppy Martine, once a traditional spiritual leader, longed to read the Bible for himself. He prayed and even fasted for God’s help to learn. Over time, his prayers were answered: He became a strong reader and later a pastor who led a new congregation!

Another new reader told a teacher with a joyful smile, “Last night I lay by the hogan fire and read nearly all night!” Moments like these showed translators that the written Word was truly taking root in people’s hearts.

Similarly, there was a middle-aged woman who had never learned to read but deeply desired to know God’s Word for herself. She studied at the team’s home almost every evening throughout one winter. Her progress was slow, but she was not ready to give up.

She prayed even more earnestly and kept practicing. By spring, her persistence and prayers were rewarded; she could read simple passages. After 10 years of persistence, she learned to read Navajo, and her first Navajo New Testament was well-loved from how often she used it.

The Dedication of the Navajo New Testament

By September 1954, the team’s work was complete, and the manuscript went to the American Bible Society. After extensive proofing, the Navajo New Testament was printed and, in September 1956, dedicated at the Christian Reformed Navajo Chapel in Farmington, New Mexico.

That night, the chapel overflowed with people. Others stood outside in the dark, listening. Copies of the New Testament were placed in the hands of Navajo believers who now could read and understand God’s Word in their own language.

One person who had studied for several years in a Bible school said:

“[The New Testament] used to be all blurred and dark to me when I read it in English, but now it is as clear as light because I understand it.”

Other people who had only known the narratives of the Gospels were astonished by the depth of the epistles. One woman admitted, “I used to think I was a pretty good Christian, but now that I’ve read what God really expects of me, I see that I’m not.”

Lasting Impact

The translation’s impact was immediate and lasting. Churches grew, families read Scripture together and people’s faith deepened in ways that are only possible when the gospel is understood in a language that touches their hearts.

Faye Edgerton’s vision, formed years prior in Korea and fulfilled in the deserts of the Southwest United States, became a legacy — not just of translation work, but of cultural respect, perseverance and love. The Navajo New Testament is a powerful reminder that when God’s Word is truly understood, it changes everything.