Years ago, in a small village in southern Senegal, Tida walked down a clay road, holding her young son by the hand as he toddled along in tow. Orange dust kicked up underfoot as she passed the cement block homes and sagging wooden fences of her family, friends and neighbors. She was on her way to meet her friend, Soutoucou.

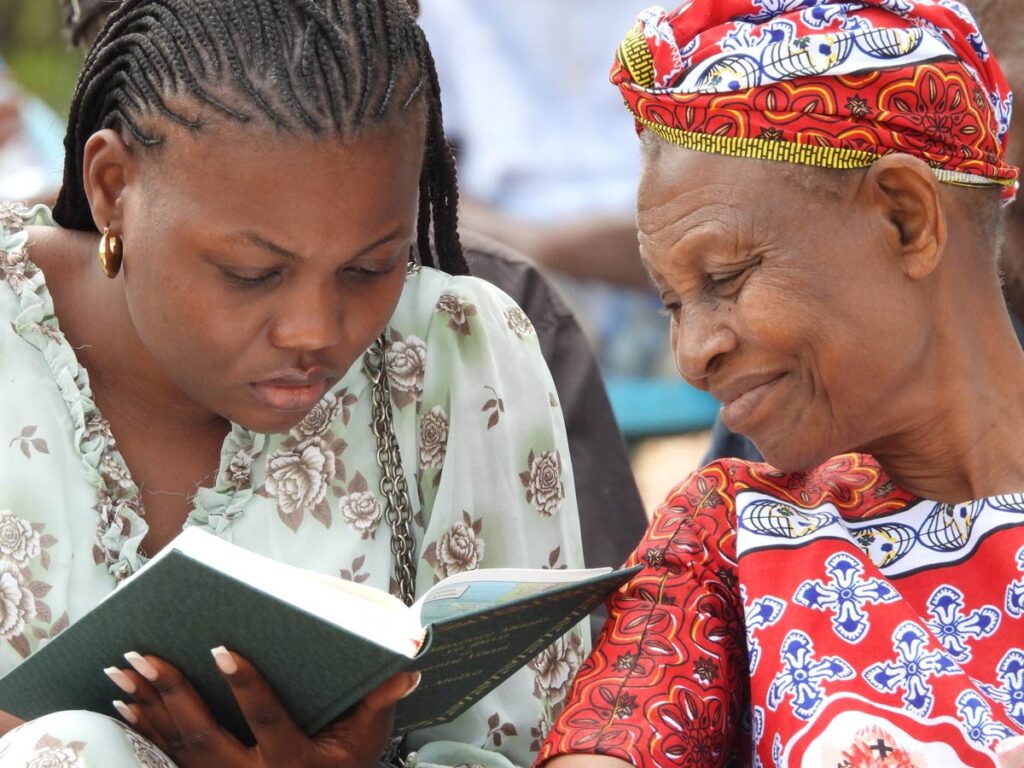

From the outside, the two women looked similar to any other women you might come across in a remote Senegalese village, dressed in brightly colored tops, head ties and ankle-length pagnes wrapped around their legs. But on the inside, they’d been changed. They were pioneers and innovators for their people.

As the ladies settled into some chairs behind a compound shared by several families, they were unfazed by the sounds of a donkey braying, the chickens clucking and roaming about their feet and the loud chatter from the crowd that formed nearby. They were at home there, and the whole neighborhood knew about the transformation that happened — transformation these women helped create with a garden and a plan.

“The market garden,” they called it. Tida, Soutoucou and a handful of other women worked together to grow produce like tomatoes, okra, corn, carrots and onions. Then they sold it at the local open-air marketplace. It wasn’t complicated, but it was significant.

In a culture where men are the primary breadwinners and decision-makers, and women rarely hold positions as thought leaders or business owners, the market garden women found a way to empower themselves, help support their families and set examples for their community.

“It’s really a great thing for us, the market garden,” Soutoucou beamed. “There is … a respect between us and our husbands.”

Literacy Opens Doors for Women and Families

But just a few years prior, these women had a very different story. With no education and no example to follow, Soutoucou, Tida and their friends lacked the skills and confidence to run a business. What made the difference?

Literacy.

Wycliffe funded a literacy program, coordinated by SIL, in their village that provided the chance to read and write their language for the very first time. Tida was well into her thirties before she saw her own language written down or learned to read it.

“The study of Manjak language is very worthwhile,” Tida said. “It’s very important for us who were blind [unaware]. We didn’t see how to learn, but with this language [class], it’s very worthwhile.”

Twenty women attended the class, all hoping to learn more about their language and enjoy it in its written form. But many came away with much more: the ability to write notes about customers, products and payments; and some new skills in organization and teamwork. Women once divided by jealousies and rivalries reconciled while taking the class and began working together.

Most importantly, they gained the confidence to take a risk and create something that put their new skills to use and could benefit the whole community.

“Studying Manjak is really important,” Soutoucou said. “Before, we were blind; we weren’t instructed. Our ancestors didn’t go to school, but today, with this teaching in Manjak, really that helped us to understand. We were blind … but now we are fully aware. Then we did the market garden, and that — the gardening we did — really helped us with our need.”

Want to see how God is using literacy to change lives in Peru too?

Read Humbelina’s story of how literacy empowers women →

The news even spread to neighboring villages, and people would ask Soutoucou to come read and write for them or teach them to build similar businesses.

But what the women were most excited about was the impact literacy had on their families.

Their school-age kids attended classes taught in Senegal’s official language, French, which can be difficult for them since Manjak is their first language. To help, the women shared their Manjak texts with their kids, which helped them improve their literacy and French skills at school. Some of the kids even took their mom’s place in the Manjak literacy class.

“I love it when my kids study Manjak,” Soutoucou said. “We are here to help our children and our families.”

Building a Foundation for God’s Word

Literacy is more than just a practical skill. For Tida, Soutoucou and the other women, learning to read and write opened doors to discover confidence and respect from people, form community and create opportunities. But literacy also lays a crucial foundation for something even greater: access to the Bible in a language and format people can clearly understand.

After all, the Bible is more than just words on a page; it’s the living Word of God that has the power to capture hearts and transform lives forever.

When men, women and children are able to read their language, they’re prepared to engage with Scripture in that same language. And that Scripture changes people’s lives — not just here on earth but for eternity.

Through literacy classes, women and their families are not just gaining tools to provide for themselves; they’re also being equipped for the day when they can participate in translation work for their communities, and read and share the Bible in their language. Literacy provides skills, and Bible translation provides access to the eternal hope found in God’s Word!